Keep making mistakes (but make them hit back)

Where we start with strawberry cum and end with yoga pants.

This post is about failing well. So it makes total sense that the first thing I’ll tell you is that DNA looks like strawberry cum. Don’t ask where I learned this; here’s what I mean if you’re curious. But beyond its unfortunate appearance, the DNA replication machinery—the molecular process where entire genomes get copied—offers profound lessons about error management that extend far beyond molecular biology.

Nerdfession: I’m fascinated with how DNA polymerase catches mistakes. Not in a normal “oh that’s interesting” way, but in a “I think about this while brushing my teeth” way. I once caught myself explaining geometric base-pairing constraints at a party, completely missing the increasingly glazed looks around the table until someone politely changed the subject to psychedelics.

But here’s the thing—understanding how molecules detect errors can forever change how you handle money, relationships, and pretty much everything else that matters.

That insight came while working in the lab (I kill microbes for a living, which is less dramatic than it sounds but more satisfying). Some of these tiny organisms live under conditions that would make minimalism look decadent. Yet despite operating on basically nothing, these bacteria maintain stunning accuracy in DNA replication, which you’d think is an energetically costly process—all this checking.

How do they do it? They mostly don’t. Instead, the errors announce themselves.

The geometry of the impossible

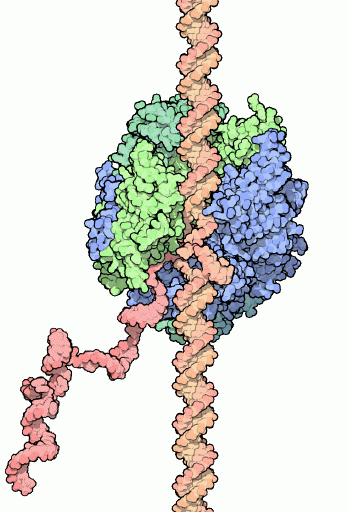

DNA polymerase is essentially a molecular copying machine—it reads one strand of DNA and builds a matching strand, letter by letter. When DNA polymerase encounters a wrong base pair, the mismatch creates a physical distortion—imagine trying to force a square peg into a round hole, except the hole can feel the wrongness and stops everything. The enzyme literally changes shape, stalls, and triggers proofreading. The constraint is the detection system. No manager, no oversight committee, no quarterly error reviews. Just physics doing the work. The above can be hard to visualize, so watch this.

Evolution has spent billions of years perfecting these microbial machines, iterating through countless designs until finding patterns that work. When we study these patterns, we’re not just learning biology—we’re discovering principles tested across geological timescales. Call it biomimicry or call it common sense, but ignoring three billion years of R&D seems foolish.

Tell me a team could design this from scratch in a year. Not fucking way. If you don’t believe in the Lindy principle—that what has survived for millennia contains wisdom we ignore at our peril—this should convert you.

However, this is the opposite of how we typically approach problems. We add monitoring systems, tracking apps, accountability buddies—layer upon layer of conscious effort to catch our mistakes. Meanwhile, three billion years of evolution keep whispering: make the error impossible, not monitored.

Poetry knew this first

Since I have cast my lot, please, golden-crowned

Aphrodite, let me win this round!

Sappho wrote that 2,600 years ago (translation by Aaron Poochigian). Notice the rhyme—it replaces the hexameter of the ancient Greek, but serves the same function, as a device that makes any copying error immediately obvious. Drop a syllable, and everyone knows.

Or consider Dr. Seuss, who famously wrote The Cat in the Hat using only 236 different words to win a bet with his publisher. The constraint forces a rigid rhyme scheme that made any deviation immediately jarring: “The cat in the hat / Came back with a bat” works; “The cat in the hat / Came back with a baseball implement” certainly does not.

Before writing, humans transmitted culture through memorized (poetic) verse. Not because they were more artistic, but because poetry’s constraints—meter, rhyme, alliteration—made errors immediately obvious. The constraint doesn’t just detect the error but makes it aesthetically painful, rhythmically wrong, obviously broken.

The assert philosophy

More recently, programmers discovered this principle: NASA’s Power of 10 coding rules mandate “a minimum average of two runtime assertions per function.” An error should crash the entire program rather than propagate silently. The assert is the geometric constraint of code—a condition that must stop the system and trigger a response.

So fucking what, get to the point already

We have DNA polymerase stalling on mismatches, Sappho’s meter catching corrupted verses, and programmers crashing entire systems rather than letting errors hide. Beautiful. Elegant. Completely useless if you’re just trying to stop buying shit you don’t need on Amazon at 2 AM.

Here’s the thing: every example above—from molecules to poetry to code—represents the same fundamental insight. They all refuse to let errors pass silently. They make the wrong thing physically, aesthetically, or systematically impossible. And while you probably aren’t transmitting epic poetry or replicating DNA strands in your daily life (I hope?), you are constantly making small errors that can compound into large failures.

The problem is that modern life has been explicitly designed to remove these natural constraints. Your credit card company wants you to overspend silently. Social media wants you to scroll without friction. Food delivery apps want ordering to be effortless. We live in a world optimized for frictionless consumption and silent failure.

But you can retrofit these ancient principles onto modern problems. You can create your own geometric constraints, your own poetic meters, your own system crashes. You just have to be willing to make certain failures impossible rather than unlikely, immediate rather than eventual, structural rather than motivational.

Let me show you what this looks like in practice.

Your budget doesn’t need willpower

Here’s what changed my financial life: I got a separate debit card that gets loaded with my discretionary spending budget each month. That’s it. That’s my only payment method saved on Amazon, on my phone, everywhere. When it’s empty, purchases literally fail. No checking balances, no guilt, no “I’ll just use my credit card this once.” The constraint surfaces the error—overspending—through the brutally elegant mechanism of card declined. A similar hack is the yearly subscription audit: Instead of checking your bank statements, reissue your credit card, and all failing subscriptions will surface, no energy needed.

Time to constrain ... time

The Pomodoro Technique involves working for 25-minute focused intervals followed by short breaks—named after those tomato-shaped kitchen timers. I’ve been using an hourglass for years now (yes, the sand-flowing kind, it looks more intellectuous). The timer’s real genius isn’t time management. Yes, I know it’s intellectual. It’s when the sand runs out after 25 minutes that you’re confronted with undeniable reality. Either you made progress or you spent the time reading about Taylor’s private life on Wikipedia.

But here’s where the real magic happens: when you continually fail to complete tasks in your allocated time blocks, the constraint doesn’t just reveal failure—it surfaces problems: Maybe you consistently underestimate how long things take, revealing a planning problem. Perhaps you’re being interrupted constantly, indicating an environmental issue. Or perhaps the task has grown more complex than you initially understood, which is still a planning problem, just a different flavor. The beauty is zero self-monitoring. The timer surfaces them automatically through repeated collision with reality.

Expensive skips

The most effective fitness programs often involve prepaying for classes with steep cancellation fees—imagine $65 down the drain for missing a session. Suddenly, skipping a workout isn’t a silent slide into the couch—it’s a specific financial wound. The error (not exercising) surfaces as immediate pain (money leaving your account). Commitment contracts take this principle to its logical extreme.

Similarly, consider the recent trend of wearing yoga pants as everyday attire—beyond the comfort factor, there’s an unspoken constraint at work. When your default wardrobe consists of form-fitting athletic wear, your body becomes its own monitoring system. Weight gain announces itself through literal discomfort before it becomes a health issue. The waistband that dug in slightly yesterday demands attention today. It’s the opposite of elastic waistbands that expand silently with you—these clothes create immediate physical feedback about changes in your body. Brutal? Maybe. But the constraint makes physical changes impossible to ignore.

Find your physics

The principle is deceptively simple: stop trying to monitor your errors and start making them impossible or immediately painful. This isn’t about self-punishment—it’s about creating systems that surface problems automatically, the way a mismatched base pair distorts the double helix.

What I love about DNA polymerase is that it doesn’t apologize for its constraints. It doesn’t try to be flexible or accommodating. When something doesn’t fit, it stops. Period. And because it stops, errors get caught before they propagate into mutations.

We need more of this geometric stubbornness in our lives. Not the kind that comes from willpower or discipline—those are exhausting and unreliable. But the kind that comes from physical, structural, unavoidable constraints that make errors impossible to ignore.

Your checking account will never judge you. Your calendar doesn’t care about your excuses. A timer has no opinions about your productivity philosophy. They just create the conditions where errors announce themselves, loudly and immediately, before they compound into disasters.

The bacteria figured this out billions of years ago. The ancient poets knew it. Toyota’s production line implements it. Maybe it’s time we caught up.

Stop checking. Start constraining.